design disables

EXCLUSIVE DESIGN

‘Exclusive Design’ is a commentary on the state of design today and a plea for designers responsibility for inclusive design.

As designers, we have an enormous impact on the relationships within our society. It is up to us to make sure that this influence is positive. For this, it is necessary that designers take more responsibility for inclusive design. We need to take on the challenge of inclusivity and accessibility and treat it as a core element of our design process, because when we design inclusively, we all benefit.

Being disabled is not a condition

but a feeling.

Our environment determines participation, involvement and inclusion within our society. Every object determines who can interact with it and who is excluded. If we design our environment in a way that makes it difficult or impossible for groups of people to participate, we hinder them. For everyone to be a self-determined and equal part of society, designing inclusive environments should be seen as the ultimate goal of design, not a barrier.

Furthermore, everyone is susceptible to temporary or permanent limitations; we all grow old at some point, are just one illness or accident away from no longer conforming to the perceived "norm," and require appropriate objects to perform even the most

basic of everyday tasks.

To communicate this need to the design community, the monobloc plastic chair became our communication medium. The chairs were altered by slightly deforming and modifying them so that sitting becomes an uncomfortable, exclusive experience. They hinder the users not only physically, but also psychologically. The five different chairs create the feeling of being disabled in different ways and draw attention to the complexity of our taken-for-granted relationship to everyday objects. In the process, existing

privileges are reflected upon.

but a feeling.

Our environment determines participation, involvement and inclusion within our society. Every object determines who can interact with it and who is excluded. If we design our environment in a way that makes it difficult or impossible for groups of people to participate, we hinder them. For everyone to be a self-determined and equal part of society, designing inclusive environments should be seen as the ultimate goal of design, not a barrier.

Furthermore, everyone is susceptible to temporary or permanent limitations; we all grow old at some point, are just one illness or accident away from no longer conforming to the perceived "norm," and require appropriate objects to perform even the most

basic of everyday tasks.

To communicate this need to the design community, the monobloc plastic chair became our communication medium. The chairs were altered by slightly deforming and modifying them so that sitting becomes an uncomfortable, exclusive experience. They hinder the users not only physically, but also psychologically. The five different chairs create the feeling of being disabled in different ways and draw attention to the complexity of our taken-for-granted relationship to everyday objects. In the process, existing

privileges are reflected upon.

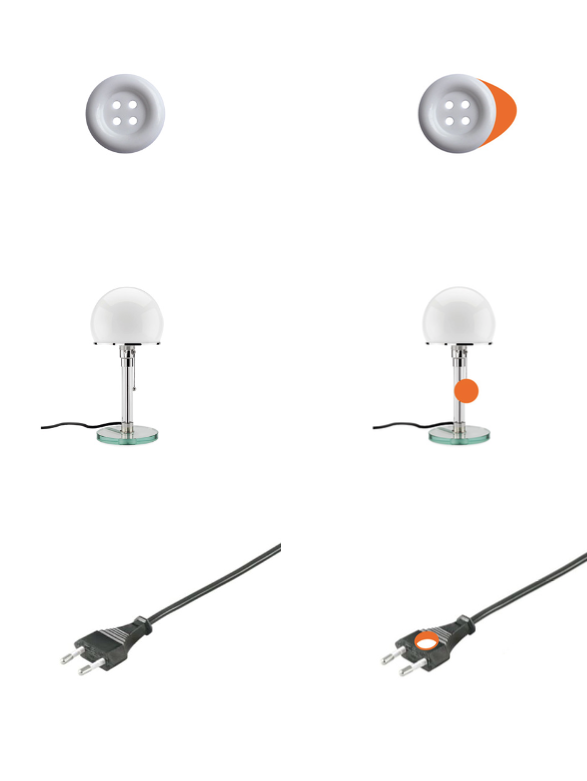

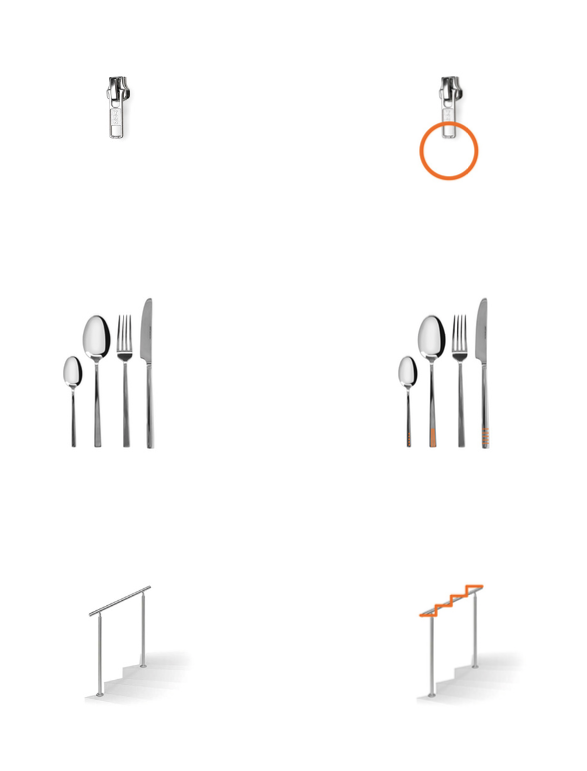

In our search for inclusive design, we found many misappropriated, homemade, or parasitic solutions. Even open source offers are characterized by their special solution character. The demand on designers to find what works for all remains a great social challenge. In this context, all those who recognize and remedy deficiencies in the relationship between people and the environment are already inclusive designers.

Our collection of everyday objects demonstrates that even the smallest changes are enough to make a product more participatory, accessible, and inclusive. Browsing through the collection is an opportunity to take the first step toward inclusive design. Simply looking at everyday objects from the perspective of inclusion is often enough to identify design potential. Thus, we understand this collection, in addition to our criticism of the present, as a confident outlook on an inclusive environment.

Our collection of everyday objects demonstrates that even the smallest changes are enough to make a product more participatory, accessible, and inclusive. Browsing through the collection is an opportunity to take the first step toward inclusive design. Simply looking at everyday objects from the perspective of inclusion is often enough to identify design potential. Thus, we understand this collection, in addition to our criticism of the present, as a confident outlook on an inclusive environment.